The policy also states that Chrome allows third-party websites to access your IP address and any information that site has tracked using cookies. Contrast that to Chrome’s privacy policy, which states that it stores your browsing data locally unless you are signed in to your Google account, which enables the browser to send that information back to Google. Its mission is to help build an internet in an open-source manner that’s accessible to everyone–and where privacy and security are built in. Unlike Chrome, Firefox is run by Mozilla, a nonprofit organization that advocates for a “healthy” internet. But I only remembered it existed recently while reporting on data privacy. It’s not a new option among internet privacy wonks. But why should I continue to use the company’s browser, which acts as literally the window through which I experience much of the internet, when its incentives–to learn a lot about me so it can sell advertisements–don’t align with mine?įirefox launched in 2004. Chrome has about 60% of the browser market, and Firefox has only 10%.

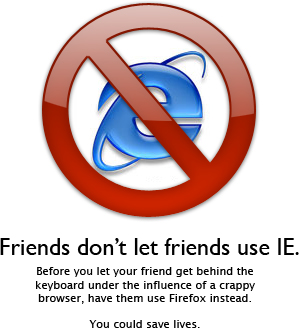

The browser has become such a default for American internet users that I never even questioned it. I can’t even remember why I decided to use Chrome in the first place. I use Duck Duck Go as my primary search engine because I’m aware of how much information about myself I voluntarily give to Google in so many other ways. Google already runs a lot of my online life–it’s my email, my calendar, my go-to map, and all my documents. What’s a concerned citizen of the internet to do? Here’s one no-brainer: Stop using Chrome and switch to Firefox. While the amount of data about me may not have caused harm in my life yet–as far as I know–I don’t want to be the victim of monopolistic internet oligarchs as they continue to cash in on surveillance-based business models. And given the number of data breaches that have occurred over the past decade, there’s a good chance that malicious hackers have my info–and if they don’t, it’s only a matter of time. I’ve watched companies shut down their European branches because Europe’s data privacy regulations invalidate their business models. So how do you walk the line between taking advantage of the internet’s many benefits while protecting yourself from the corporate interests that aim to use your data for gain? This is the push-and-pull I’ve had with myself over the past year, as I’ve grappled with the revelations that Cambridge Analytica has the personal data of more than 50 million Americans, courtesy of Facebook, and used it to manipulate people in the 2016 elections.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)